Synopsis

Synopsis

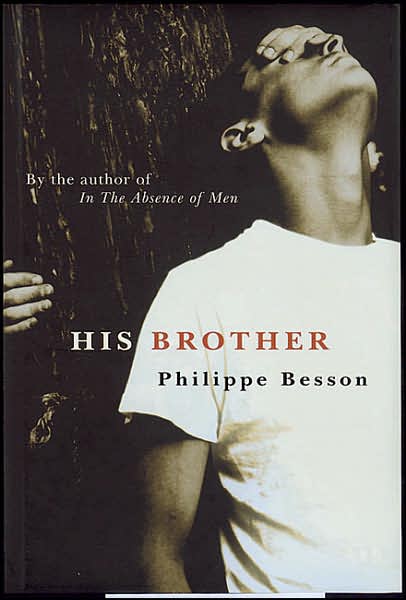

Lucas’s brother Thomas is dying. At their childhood holiday home, the two brothers wait for Lucas to die. Besson’s dispassionate observation of disease and death is haunting, as he portrays the inability of others to cope with Thomas’ illness and the petty cruelties of the medical system. Interwoven with the chronicle of Thomas’ death are the brothers’ memories of their childhood and adolescence, their jealousies and rivalries, their unspoken bond. As those around them withdraw from this inexplicable, inexorable death, Lucas and Thomas retreat to their childhood paradise to wait for the end.

Besson’s second novel to be translated (it is in fact his third) is a spare account of a beloved brother’s untimely death. which has the sensory impact of a memoir – so much so that I assumed (quite wrongly, as it turned out) that it must be autobiographical.

Praise for “His Brother”

Lucidly translated, the story takes the form of nonchronological diary entries written over a time period of several months, from March, when the narrator’s younger brother, Thomas Andrieu, 26, undergoes a series of tests for “spontaneous haemorrhage,” until early September, when the young man will die of a mysterious blood disease (not AIDS). Over the spring and early summer, he is hospitalized and put through a series of ignominious procedures, such as a sternal tap involving “implements of torture,” infusions of immunoglobulin and corticosteroid treatment. He is released briefly but grows precipitously worse. The spleen is announced as the culprit, and a splenectomy performed-to no avail. Lucas, his older brother by a mere 15 months, watches Thomas suffer in silent agony, notes the friends falling away from him, including his flighty, green-eyed girlfriend Claire (Lucas’s lover, Vincent, deserts him as well). Clear-eyed and unflinching, Lucas records the visits of their ineffectual parents, whose own grief becomes selfish and crippling. As children, the brothers spent their summers on the Atlantic coastal island of ele de Re, and Lucas’s narrative weaves in early memories of the two brothers, often taken as twins. Now, having accepted Thomas’s disease as incurable, the two return, in late summer, to Saint-Clement-des-Baleines to pass the last days of Thomas’s life. There, they regularly encounter an old man on the beach whose own life is “littered with corpses.” Thomas has a theory that his illness is a kind of reckoning, and the old man’s edict that “you don’t defy the will of the ocean” at last allows him to face his death. Besson’s prose has a fatalistic Greek gravitas and a stark honesty: a moving novel as memoir.

Kirkus Reviews