Recommended by PEN

Recommended by PEN

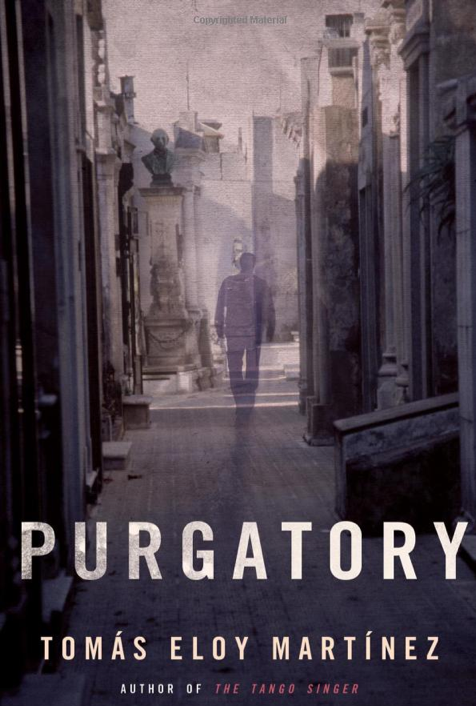

‘Simón Cardoso had been dead for thirty years when Emilia Dupuy, his wife, found him at lunchtime in the dining room of Trudy Tuesday.’ So begins Martínez’s most moving, most autobiographical novel: a ghost story, the ghost story which has been Argentina’s history since 1973. Simón, a cartographer like Emilia, had vanished during one of their trips to map an uncharted country road. Later testimonies had confirmed that he had been one of the thousands of victims of the military regime – arrested, tortured and executed for being a “subversive.” Yet Emilia had refused to believe this account, and had spent her entire life waiting for him to reappear. Now in her sixties, the Simón she has found is identical to the man she lost three decades ago. While skirting around the mystery, Eloy Martínez masterfully peels away layer upon layer of history –both personal and political. Just as Simón’s disappearance comes to represent the thousands of disappearances that became such a common occurrence during the dictatorship, so Emilia’s refusal to accept his death mirror’s the country’s unwillingness to face its reality.

Reviews

I last saw Tomás Eloy Martínez in 2009, in Buenos Aires, a few months before his death the following year. He told me he was trying to write a novel about the Argentinian dictatorship that bled the country from 1976 to 1982, but that he wanted to do it without descriptions of atrocities, without depictions of rape and torture – rather a recreation of what it felt like “to breathe in the contaminated air” of the time. “Living inside history,” he said, “we miss the obvious. For the actors of history, the obvious is what is always absent. I wish I could write that.” In Purgatory, splendidly translated by Frank Wynne, his last wish was granted.

The posthumous publication of Purgatory shows a writer at the height of his craft, and is a fitting conclusion to the work of one of Latin America’s most remarkable novelists.

Alberto Manguel Guardian Friday 13 January

ORSON WELLES has an unlikely cameo in this novel about the long aftermath of Argentina’s Dirty War, and Tomás Eloy Martínez gives him perhaps its most important line: “Things exist only when we see them.” The last book Eloy Martínez wrote before he died in 2010, now limpidly translated by Frank Wynne, it explores the hazy No Man’s Land between how things appear and how they are. If that sounds like a recipe for metaphysical hocus-pocus, don’t be put off. “Purgatory” is an intriguingly circuitous, occasionally confounding but more often poignant story of loss.

ORSON WELLES has an unlikely cameo in this novel about the long aftermath of Argentina’s Dirty War, and Tomás Eloy Martínez gives him perhaps its most important line: “Things exist only when we see them.” The last book Eloy Martínez wrote before he died in 2010, now limpidly translated by Frank Wynne, it explores the hazy No Man’s Land between how things appear and how they are. If that sounds like a recipe for metaphysical hocus-pocus, don’t be put off. “Purgatory” is an intriguingly circuitous, occasionally confounding but more often poignant story of loss.

Emilia Dupuy is a middle-aged woman living in New Jersey, an exile from Argentina. Her father, Dr Orestes Dupuy, was the chief propagandist for the military junta that terrorised Argentina between 1976 and 1983, when thousands of people became desaparecidos, the disappeared. Among them was Emilia’s husband. She spends the next 30 years looking for him—her purgatory, “a wait whose end we cannot know”—sustained by a sense that he survived.

Narrated by a novelist, himself an exiled Argentine who sounds not unlike Eloy Martínez, the story takes us from Emilia’s life in America to her past in Buenos Aires, and from her testimony to novelistic invention. Sometimes Eloy Martínez lingers too long on a scene, and the sex is more fun for the characters than for the reader. But “Purgatory” is a compassionate novel about the power of chimeras—of what we choose to see, of what we can bear to see—and the way grief clots when it is unresolved.

The Economist, 9 November 2011.

Martínez, who was shortlisted for the inaugural International Man Booker Prize, in 2005, died early last year. He was an opponent of the Perónist regime, and from 1976 until 1982 he lived in exile in Venezuela. Purgatory , his final novel, is arranged in five almost self-contained acts, all shifting gracefully and ironically between realism and the surreal. No matter how strange and alluring it becomes, the narrative never conceals the horrors Argentina suffered under the rule of the generals. Yet Martínez has written a romance, not a polemic. That said, it is a love story with a fist at its centre. […]

This is an unusual work in that it begins well and gets better and better. Martínez is not above sly humour, and he extracts abundant grotesque humour from Dr Dupuy’s scheme to commission Orson Welles to direct a propagandist documentary about Argentina to publicise the 1978 World Cup. Welles is more than a match for him, and begins speaking about the illusion of film, the sheer magic. Dupuy reckons he has his man. But Welles, “call me Orsten” – is depicted as shrewd and rather magnificent: “I’ll bring my magic to this documentary, you pay me with your magic.” For once Dr Dupuy is confused and admits, “I still don’t understand, Orsten.” Welles replies, “I make the film for you for free, with the best World Cup anyone’s ever seen, and you and your generals will make the disappeared appear.”

Late in the novel the narrator realises that the more he delves into Emilia’s life, “the more I realise that from beginning to end it is an unbroken chain of losses, disappearances and senseless searches. She spent years chasing after nothing . . . But aren’t we all like that?” Such a reflection adds a philosophical dimension to the fact that Emilia is a metaphor for Argentina.

One small quibble is to do with the repetition of the fear that the mirrors in her mother’s dressing room held for Emilia both as a child and as an adult. It should have been dealt with in the original edition. It is a minor stylistic lapse in a bravura performance from a courageous artist whose wit always tempered his anger. Purgatory follows Emilia through her private hell in Martínez’s personal love song to his country.

Eileen Battersby, The Irish Times